The Kid Who Started with Nothing

You know how some people just seem destined for greatness? Graham Dickie wasn't one of those kids. When he first picked up a camera during his college years, nobody would have predicted he'd end up shooting for The New York Times. His story is proof that sometimes the best journeys begin with the most ordinary moments.

Graham's first camera wasn't some fancy DSLR his parents bought him for his birthday. It was actually a beat-up film camera he found at a garage sale for twenty bucks. The thing barely worked, but something about holding it just felt right. He spent hours walking around campus, shooting random stuff - his friends eating pizza, pigeons on benches, shadows on brick walls. Nothing earth-shattering, just a college kid figuring things out.

The turning point came during his junior year when he switched majors completely. One day he was studying business, the next he was telling his parents he wanted to pursue photography full-time. You can imagine how that conversation went over at the dinner table. But Graham had captured this incredible shot of students protesting on campus that ended up getting shared over ten thousand times on social media. That's when he realized he had something special.

Like every beginner, Graham made his fair share of mistakes. He'd show up to shoots with dead batteries, forget his memory cards, and don't even get me started on his early editing attempts. But here's the thing about Graham - he learned from every single screw-up and kept pushing forward.

What Makes His Photos Actually Good

If you've seen Graham's work on Instagram or in the Times, you know there's something different about his photos. They don't just look pretty - they tell stories that make you stop scrolling and actually pay attention. That's not an accident.

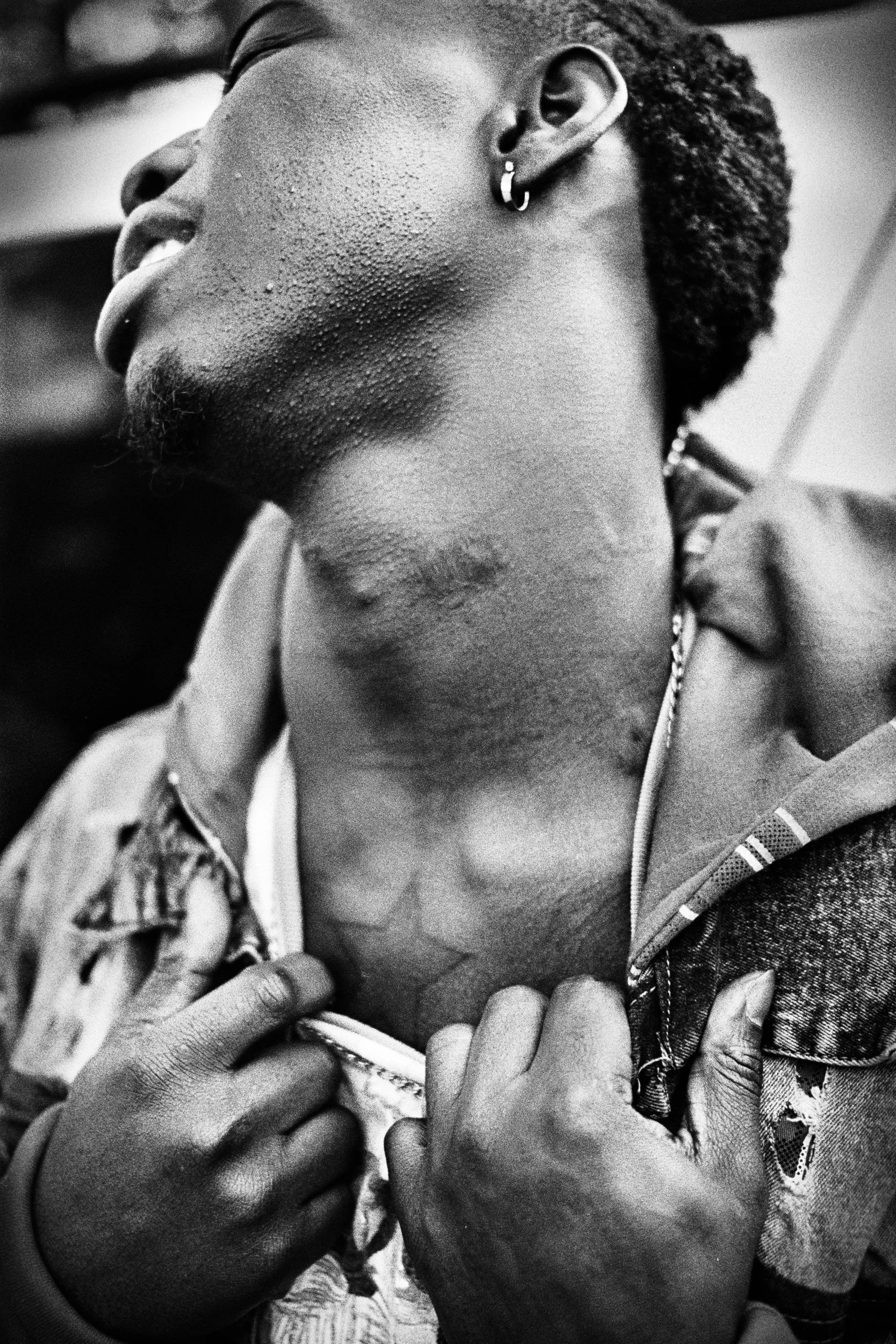

Graham figured out early on that people connect with authenticity way more than perfection. While other photographers were obsessing over getting every technical detail perfect, he focused on capturing real moments and genuine emotions. His photos feel like you're right there in the scene, not like you're looking at some overly polished advertisement.

His gear setup might surprise you too. Sure, he's got professional equipment now, but Graham still believes that a good photographer can create magic with pretty much any camera. He's got this rule where he practices with just one lens for weeks at a time, forcing himself to get creative with composition instead of relying on fancy equipment to do the work.

The editing style that made him famous on social media came from hours of experimenting with different apps and techniques. He'd spend entire weekends just playing around with color grading, trying to find that perfect balance between eye-catching and natural. The breakthrough came when he started treating his photos like short stories - each edit decision had to serve the narrative he was trying to tell.

The Rough Patches Nobody Talks About

Here's what they don't show you in those inspiring success posts - Graham almost quit photography completely about three years into his career. He'd been freelancing for months, getting rejected left and right, and his bank account was looking pretty sad. The worst part was this portfolio review where the editor basically told him his work looked like "every other Instagram photographer out there."

That criticism hit hard because Graham knew there was some truth to it. He'd been playing it safe, shooting what he thought people wanted to see instead of developing his own voice. For three months, he barely touched his camera. He was seriously considering going back to finish that business degree his parents were still hoping he'd complete.

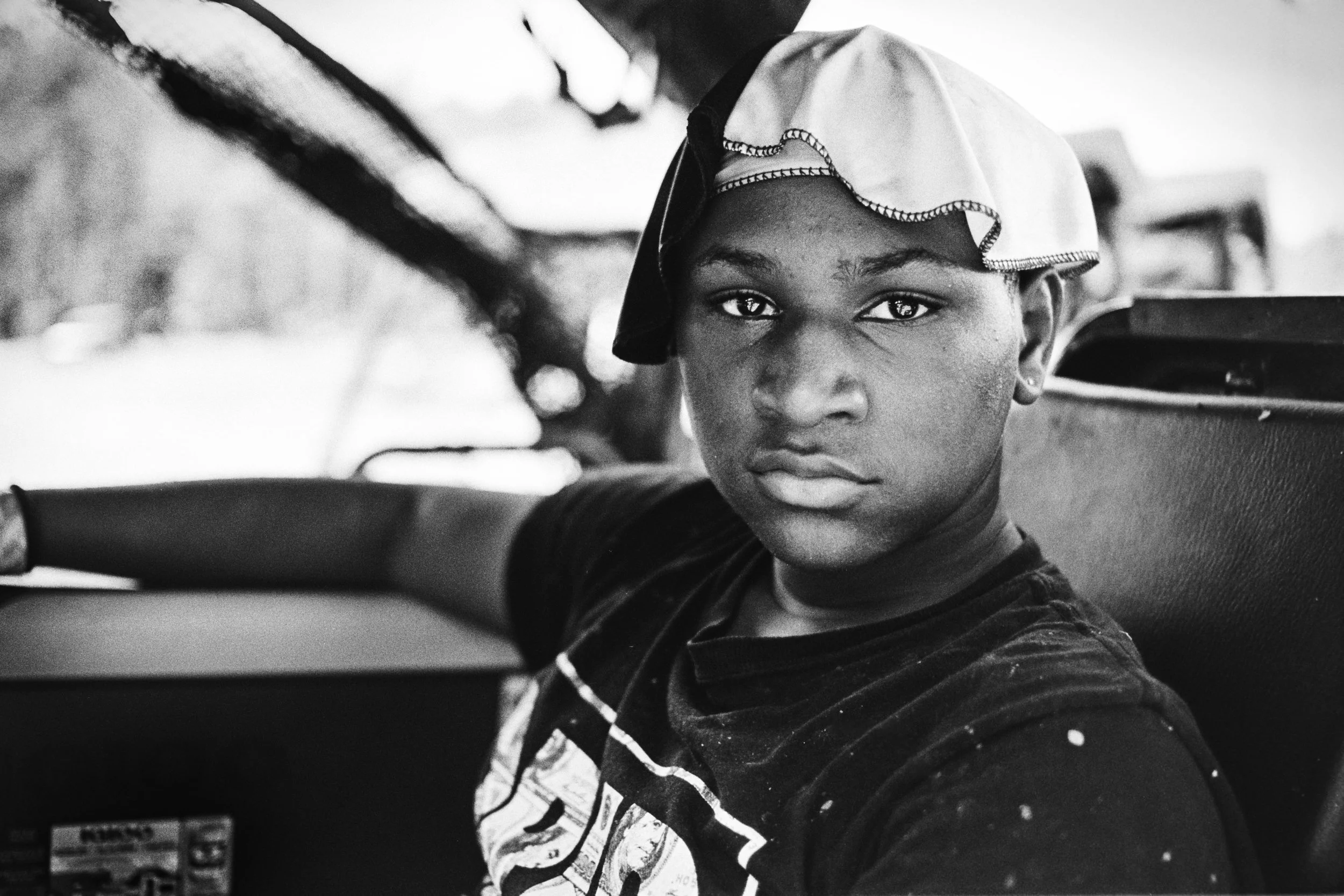

The comeback story is where things get interesting though. Instead of giving up, Graham decided to completely reinvent his approach. He started saying yes to weird assignments nobody else wanted - photographing local band practices in dingy basements, documenting community events in rough neighborhoods, covering stories that bigger publications ignored.

That's when his real style started emerging. The gritty, authentic feel that would later become his signature wasn't some calculated artistic choice - it came from shooting in challenging conditions with limited resources. He learned to find beauty in unexpected places and tell compelling stories about people most photographers wouldn't give a second glance.

The Call That Changed Everything

Graham still remembers exactly where he was when his phone rang with the opportunity that would change his career forever. He was eating cereal in his tiny apartment, scrolling through job listings and feeling pretty sorry for himself, when a Times editor called about a breaking news assignment.

They needed someone who could get to a location fast and capture the human side of a developing story. Graham had built a reputation for being reliable and quick on his feet, qualities that matter way more than fancy credentials when news is breaking. He grabbed his gear and was out the door in fifteen minutes.

That first assignment led to another, then another. What impressed the editors wasn't just his technical skills - it was his ability to connect with people in difficult situations and capture moments that told the bigger story. Graham has this gift for making subjects feel comfortable even when cameras usually make them nervous.

Some of his most powerful work has come from these breaking news situations where he has to think fast and trust his instincts. There's this one photo from a community rally that ended up getting retweeted hundreds of thousands of times. The crazy part is he almost didn't take the shot because he thought it was too simple. Sometimes the most impactful images are the ones that feel effortless.

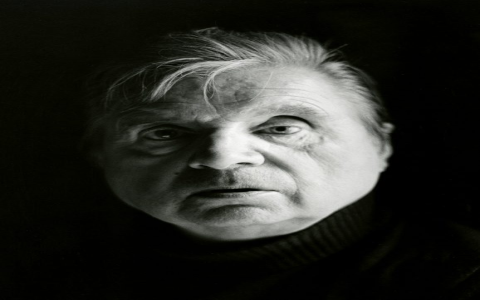

Working with celebrities and public figures brought its own set of challenges. Graham learned quickly that the key to getting authentic shots of famous people is treating them like regular humans, not putting them on a pedestaldestal. Some of his favorite portraits have come from those quiet moments between the official poses when subjects let their guard down.

Building Skills That Actually Matter

If you asked Graham what really made the difference in his career, he'd probably say it wasn't any formal training or expensive workshops. YouTube University taught him more about practical photography than most traditional programs ever could. He'd spend hours watching creators break down their techniques, then go out and practice until he could execute those concepts in his own style.

The mentors who shaped his vision weren't necessarily famous photographers either. There was this local newspaper photographer who showed him how to anticipate moments before they happened. A wedding photographer taught him about working with natural light. An art teacher from college helped him understand composition in ways that stuck with him years later.

Graham's daily practice routine is surprisingly simple. He commits to taking at least one meaningful photo every single day, even if it's just with his phone during lunch break. The goal isn't to create masterpieces constantly - it's to keep his creative muscles active and his eye sharp. Some days it's just documenting his coffee cup, other days it turns into an impromptu street photography session.

What really set Graham apart was realizing that modern photographers need skills beyond just taking pictures. He taught himself basic business principles, learned how to write compelling captions for social media, and figured out how to network without being that annoying person who only talks about themselves. These soft skills opened doors that pure technical ability never could have.

When Hard Work Gets Recognized

The first major recognition Graham received came from a photography competition he almost didn't enter. He was scrolling through submission guidelines thinking his work wasn't polished enough when a friend literally threatened to submit his photos for him if he didn't do it himself. That winning shot started conversations with editors and other photographers who became important connections in his career.

What Graham learned about competitions is that winning isn't even the most valuable part - it's the feedback from judges and the networking opportunities with other participants. Some of his best professional relationships started with conversations at award ceremonies or gallery openings where his work was displayed.

Social media recognition came gradually, then all at once. Graham focused on consistently sharing work that represented his authentic style rather than chasing whatever was trending. When one of his photos got featured by a major photography account, the exposure led to inquiries from potential clients and collaboration opportunities he never would have found otherwise.

The industry recognition that mattered most to Graham came from other photographers whose work he respected. Getting positive feedback from peers who understood the craft and the challenges involved felt more meaningful than any formal award. That validation gave him confidence to take bigger creative risks and pursue more ambitious projects.

Building a Brand That Feels Real

Graham's approach to building his professional reputation was pretty straightforward - be genuine, deliver good work consistently, and treat everyone with respect. He figured out early that authenticity resonates way more than trying to project some perfect professional image that doesn't match who you really are.

His social media presence grew organically because he shared the behind-the-scenes reality alongside the polished final products. People connected with seeing his failures and learning processes, not just the highlight reel. This honesty attracted clients who wanted to work with someone real rather than some untouchable artistic genius.

Networking for Graham meant having genuine conversations about shared interests rather than just exchanging business cards at industry events. Some of his best professional relationships started over casual conversations about favorite photographers or debating camera settings. When you approach networking as making friends rather than collecting contacts, the relationships tend to be much stronger.

The referral system that keeps consistent work flowing came naturally from doing right by clients and collaborators. Graham learned that going slightly above and beyond on every project creates advocates who recommend him to others. Word-of-mouth marketing is still the most powerful tool in any creative professional's toolkit.

Looking Ahead

Graham stays excited about photography by constantly exploring new techniques and technologies. He's fascinated by how artificial intelligence is changing the industry - not as a threat to replace photographers, but as a tool that might enhance storytelling capabilities. The key is staying curious and adaptable rather than getting defensive about change.

The mobile photography revolution continues to level the playing field in ways that excite Graham. Some of his recent favorite images were captured on smartphones during spontaneous moments when his professional gear wasn't accessible. The best camera really is the one you have with you, and modern phones are capable of incredible results in the right hands.

Documentary photography has become Graham's latest passion project. There's something powerful about using photography to shine light on important stories that might otherwise go untold. He's working on a long-term project documenting community resilience that combines his technical skills with his desire to create meaningful social impact.

Real Advice for Future Photographers

If Graham could go back and give his younger self advice, he'd probably start with the money conversation that nobody wants to have. Learning to price your work appropriately and have confident conversations about compensation is just as important as developing technical skills. Working for free has its place when you're building experience, but knowing when to start charging what you're worth is crucial for long-term success.

The biggest career-killing mistakes Graham sees young photographers make usually involve copyright issues or unprofessional social media behavior. Understanding your rights and protecting your work legally might not be exciting, but it's essential knowledge. And remember that everything you post online contributes to your professional reputation - future clients and collaborators are definitely looking.

Perfectionism paralyzed Graham's progress more than any external obstacle ever did. There's always going to be someone with better gear, more experience, or fancier credentials. The photographers who succeed are usually the ones who ship their work consistently rather than waiting until everything is perfect. Done is often better than perfect, especially when you're building momentum.

The opportunities available to photographers today are incredible compared to previous generations. Social media platforms provide direct access to potential clients and audiences that used to require expensive marketing budgets or industry connections. Technology has democratized both the tools and the distribution channels in ways that favor motivated individuals over large institutions.

Your Turn to Start

Graham's story proves that incredible careers can start from the most ordinary beginnings. You don't need expensive equipment, formal training, or industry connections to begin developing your skills and building your portfolio. What you need is curiosity, persistence, and the willingness to put your work out there even when it feels scary.

The best time to start is always right now. Grab whatever camera you have access to - even if it's just your phone - and start documenting the world around you. Pay attention to light, look for interesting compositions, and practice telling stories through images. Every professional photographer started exactly where you are right now.

Graham's incredible rise from garage sale camera to New York Times photographer happened one photo at a time, one small decision at a time, one day of practice at a time. Your version of that journey starts with whatever shot you take next.