So, I’ve been dealing with international money transfers for years now, both personally and for some small business stuff. It’s always been a pain, right? You send a chunk of cash, and when it arrives on the other end, it’s always less than you expected. You scratch your head and think, “Wait, where did that twenty bucks go?”

I decided to finally dig into this because it was getting ridiculous. Every wire transfer had some mysterious deduction, and the banks were totally vague about it. They’d just say “wire fees” or “receiving bank charges.” I wanted names, folks. Who is actually taking a cut of my hard-earned money?

The Initial Investigation: Talking to My Bank

First step was hitting up my own bank. I remember calling them up, pretty frustrated. I asked them straight up: “When I send a USD wire to Europe, why does the recipient always get less, even if I pay your outgoing fee?”

The first few customer service reps were useless. They kept giving me the standard line: “Oh, that’s the receiving bank’s fee.” But I pushed back. I knew the recipient’s bank wasn’t the only culprit. I demanded to know the entire path the money takes.

Finally, I got a hold of someone in the international services department—a guy named Gary, I think. Gary was actually helpful. He explained the concept of intermediary banks. This was the lightbulb moment.

Mapping the Money Trail

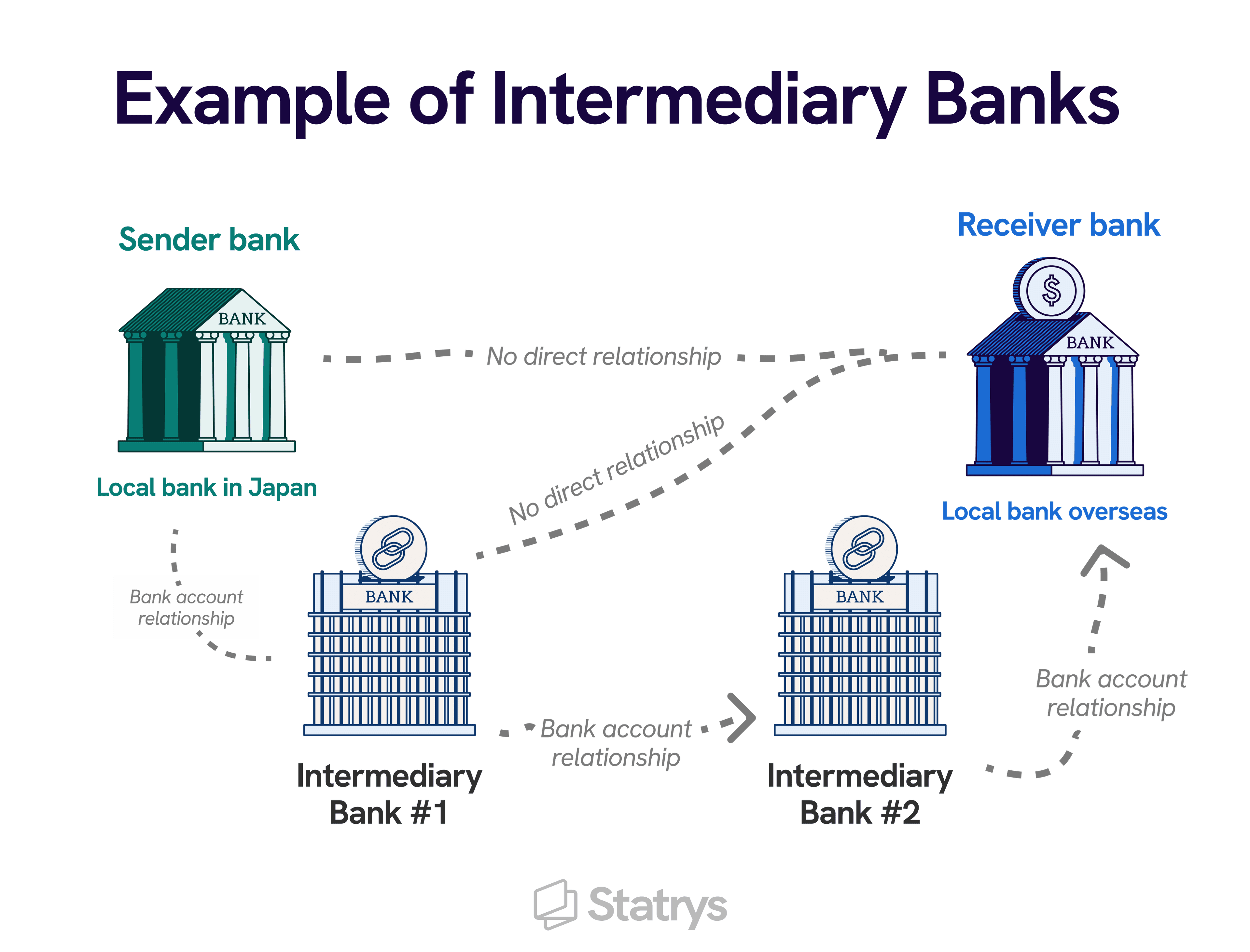

When you send a wire internationally, especially across different currency zones (like USD to EUR), your bank usually doesn’t have a direct relationship with the recipient’s bank. Instead, your bank has to use another bank—often a large global bank in New York or London—to facilitate the exchange and routing. These are the intermediary banks.

Gary explained that these big banks act as bridges. They hold accounts for thousands of smaller banks globally. When my bank sends the wire, the intermediary bank grabs the instruction, processes the currency conversion if needed, and then forwards the payment instruction to the next link in the chain, or directly to the beneficiary bank.

And guess what? They don’t do this for free. This is where the deduction happens. It’s often an unspoken, non-negotiable fee taken right out of the principal amount before it even reaches the destination country.

The Practice Run and Documentation

I decided to run a little experiment to get hard proof. I sent three identical wires of $1,000 USD to three different accounts in Europe, using three slightly different routing options (where possible, I specified ‘OUR’ fees, meaning I covered all fees, but even that wasn’t 100% effective).

- Wire 1 (Standard): Used the cheapest, standard routing my bank offered.

- Wire 2 (Specified Correspondent Bank): I asked my bank if they could use a specific, known, large bank for routing, hoping they’d have a transparent fee structure. (They couldn’t promise, but they tried.)

- Wire 3 (Via Fintech Service): I used a popular fintech transfer service just to compare the final amount received, which usually has fees baked in upfront.

The results were telling. Wire 1 arrived with about $25 short. Wire 2 arrived with $20 short. The fintech service (Wire 3) arrived almost exactly as promised, but their upfront fee was higher, about $35, which I knew about from the start.

I went back to Gary and asked for the “SWIFT confirmation copy.” This document is key. It shows the chain of banks involved. Looking at the SWIFT message for Wire 1, there it was, plain as day: a major international bank in New York was listed as the correspondent, and a small line item, often coded strangely (like “71B”), showed the deduction.

The Takeaway: Why They Get Away With It

The reason this fee is so tricky is because neither your sending bank nor the receiving bank usually tells you about it upfront. It’s a fee levied by a third party, the intermediary, and often, the exact amount isn’t known until the transaction is already processed.

They take a cut because they are providing liquidity and the network infrastructure for global transfers. Essentially, they’re renting out their relationship with the global banking system.

My final realization? If you’re sending money globally, you have two choices: either accept that hidden, unpredictable deduction by the intermediary bank, or use a service that bypasses the traditional correspondent banking system, like a dedicated money transfer provider, whose fee is paid upfront and is guaranteed, even if slightly higher. For me, knowing the exact amount that will arrive is worth the extra upfront fee. No more mysterious disappearances of my hard-earned cash.